Fat-Tailed Distributions in Finance

In most classical financial models, we assume that asset prices follow a Geometric Brownian Motion (GBM). This implies that the log returns of the asset should be normally distributed.

However, empirical data shows that log returns often follow a fat-tailed (or heavy-tailed) distribution instead.

Comparison with the Normal Distribution

The tails of a standard normal distribution decay exponentially as:

\[\mathbb{P}(|X| > x) \sim \exp(-x^2).\]In contrast, the empirical distribution of log returns places significantly more probability mass in the tails. That is:

- Extreme events (both large gains and losses) occur more frequently than predicted by the normal distribution.

- This results in a distribution with higher kurtosis (peaked center and fat tails).

Evidence from Q–Q Plots

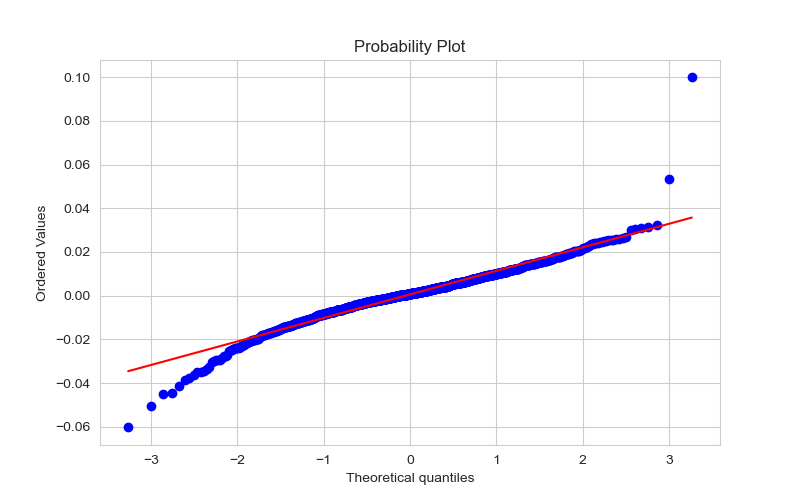

Here is the Q-Q plot against a normal distribution. We observe:

- Center of the plot follows the diagonal.

- Tails deviate sharply:

- Left tail bends downward → more extreme negative returns.

- Right tail bends upward → more extreme positive returns.

This characteristic “S-shape” or “bowtie shape” in the Q–Q plot is a signature of fat-tailed behavior.

Causes of Fat Tails in Financial Markets

Fat tails arise due to a variety of real-world factors not captured by simplistic models:

| Cause | Explanation |

|---|---|

| Information shocks | Sudden unexpected news (e.g., geopolitical events, economic reports) can cause large price movements. |

| Liquidity crises | In illiquid markets, large orders can have disproportionate price impact, amplifying tail risk. |

| Feedback loops | Mechanisms like margin calls or stop-loss cascades can cause rapid price swings. |

| Herding behavior | Investors may imitate each other, amplifying moves in one direction. |

| Volatility clustering | Periods of low volatility are often followed by high-volatility bursts, leading to heavy tails (often modeled via GARCH). |

| Leverage and derivatives | Use of leverage magnifies gains and losses, increasing tail risk. |